Just over a year ago, Lyft proudly announced it was “now a fully flexible workplace”, and that employees would “have the choice of where to live and where to work”.

In April, Lyft’s new CEO David Rishner laid off more than 1,000 employees, roughly 26% of its workforce, and mandated that the remaining staff must return to the office 3–4 days per week. The double punch has ensured his staff takes this mandate seriously.

Lyft is far from alone in issuing a directive for staff to return to the office.

Amazon is now requiring staff to work in the office at least three days a week. In April employees staged a workout in response, but the company remains undeterred in its decision.

Google has also joined the call and has made office attendance a key element of annual performance reviews if staff don’t comply with the three-day minimum for in-office work. A union has slammed the move stating “Professionalism has been disregarded in favor of ambiguous attendance tracking practices, tied to our performance evaluations”.

Regardless of how this plays out one thing is clear.

Tech, an early advocate for remote working practices is backpaddling on their position, fast.

But why is this?

Remote work limits the collaboration needed to generate disruptive ideas

Many companies argue that in-person collaboration is needed to generate disruptive ideas. And there is some evidence to support this.

A recent paper from academics at Columbia and Stanford Business Schools analyzed whether virtual teams could brainstorm as creatively as in-person teams.

They recruited about 1,500 engineers to work in pairs and randomly assigned them to brainstorm either face-to-face or over videoconference. After the pairs generated product ideas for an hour, they selected and submitted one to a panel of judges. Engineers who worked virtually generated fewer total ideas and external assessors graded their submitted ideas as significantly less creative than those of the in-person teams.

Another study from MIT and UCLA drew similar conclusions. They published a map of face-to-face interactions in the bay area, made using smartphone geolocation data, and matched it to patent citations by individual companies. They found that companies with the most face-to-face interactions also had the most unique patent citations.

It is not clear why the quality of ideas degrades when people collaborate remotely. Reflecting on my own experience, I suspect this is in part due to collaboration requiring strong social bonds between people, which are harder to develop over a virtual chat.

More broadly, when we work remotely the breadth of our interactions reduces. Evidence indicates that remote work makes people more likely to hunker down within their pre-existing teams, and less likely to engage outside of this group. This reduces information sharing and the chance to take on differing views and insights.

But it’s important to not over-generalize the need for in-person collaboration. Not all jobs are created equal. For some companies, in-person collaboration between engineers may be essential to create truly novel ideas. But for people who work in accounting, marketing, and logistics, I’m not sure the same holds true.

Now we have been shown a new way of working, what is important is to focus on how to get the best work done, in the best way for all parties.

Questions remain about how productive remote workers are

Companies are also concerned that remote working decreases productivity. The latest tech leader to weigh in on this is Paul Graham, co-founder of Y-Combinator, who suggested that while remote working can work initially if starting with a team already well-established from in-person work, productivity ultimately fades with time.

Remote workers certainly don’t agree with this point. According to a recent survey by Pew Research, 56% of respondents said working from home helps them get more work done, and reported increased levels of focus, and a better work-life balance.

It is still unclear what the long-term effects of working remotely will be on productivity. But forcing employees back to the office is not a cure for all, and there is plenty of evidence that people can work from home with no loss in productivity.

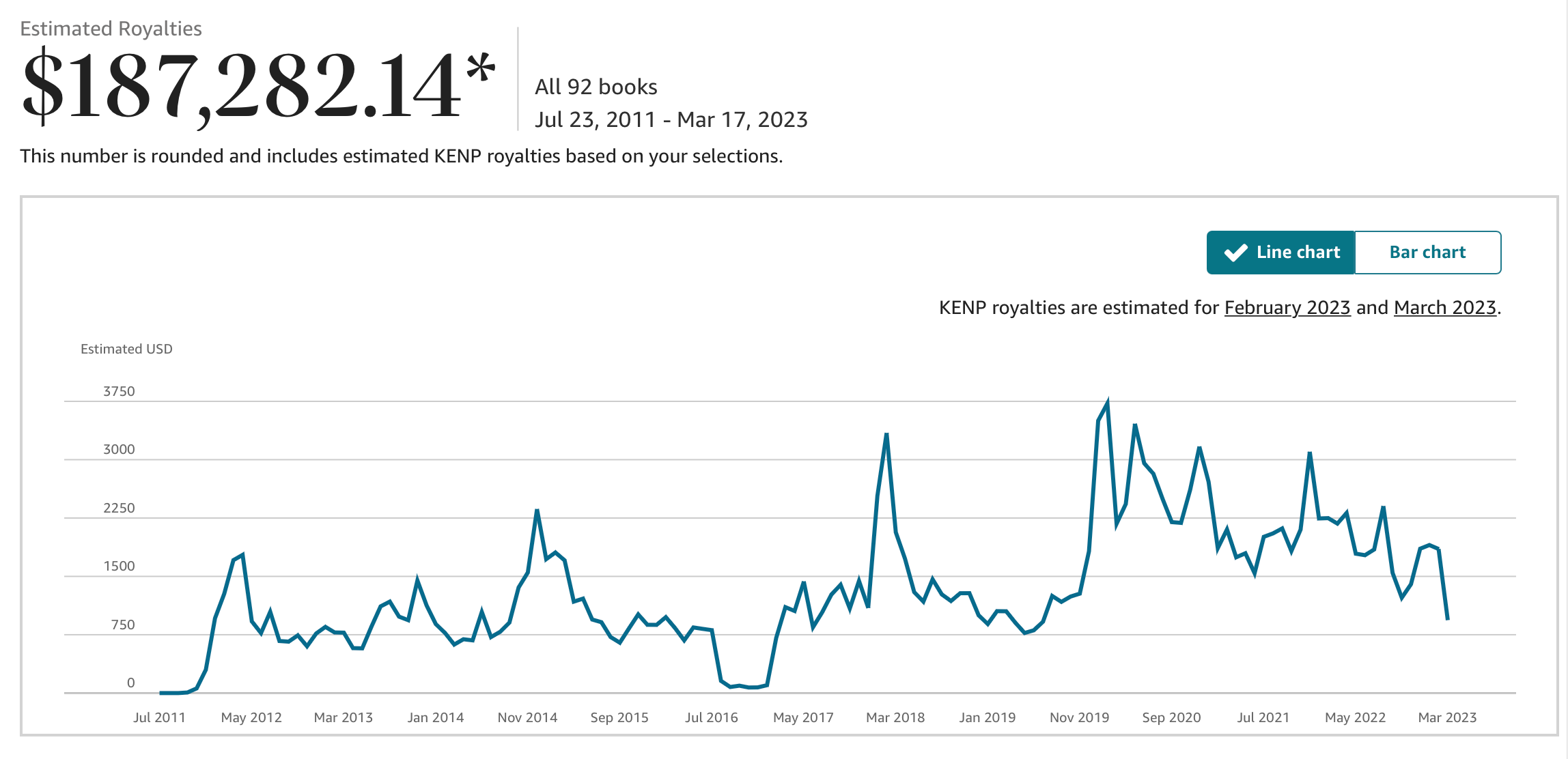

Take the worker productivity data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics as a good example. This shows that worker productivity increased sharply in Q1 2020 when we all started to work from home due to the pandemic. Those higher productivity levels remained steady until suddenly dropping in the first half of 2022, around the same time that workers began returning to work.

Remote work is a terrible way of onboarding new hires

As remote work has bedded in something has become clear — remote work is worse for new joiners. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently published an internal analysis, claiming that fully remote staff are less productive than those who had at least some in-person office time before the pandemic.

“Our early analysis of performance data suggests that engineers who either joined Meta in person and then transferred to remote or remained in person performed better on average than people who joined remotely”.

This is particularly challenging for younger workers, who often learn through osmosis, which requires in-person interaction.

Remote work is bad for our collective mental health

Lastly, remote work dissidents point out that remote work is bad for our collective mental health. Employees love to work from home until they feel isolated and alone; lacking a professional support network during times of high pressure or uncertainty.

By not going into the office, we miss out on the chance to build meaningful relationships with our colleagues and engage in much-needed social interactions — catching up in the corridor, making a tea, or popping to Starbucks.

While working from home can be great if you’re happily married with lots of social interaction at home, it can be horrible if you’re single, especially for those relocating to a new city for work.

But there is no point in these people going into the office, just to find it empty.

Employers have a responsibility to look after the collective well-being of all staff, not just those happily coupled up.

(Personally, I go to work to escape my wife, but perhaps that’s just me)

So how do we move forward and create a way of working that serves all parties?

Over the last few years, we have experienced a very different way of working. One that gives us more time to spend with loved ones, reduces stress by reducing commutes, and helps save more money.

Forcing people back to the office will likely be a mistake as it will damage the psychological contract between the company and employees, and make people feel like they can’t be trusted to work independently.

I’d argue the future of work is a hybrid model, and executives need to retrain themselves to manage teams within that reality.

One way companies could achieve this is by appointing managers solely responsible for coordinating hybrid teams. They could onboard new hires by ensuring their managers and colleagues are in the office during their first week. They could oversee the formation of hybrid teams to take on new projects. And they could plan regular retreats and away days to catalyze the development of new disruptive ideas.

Remote work isn’t going away, nor is the office. And it is important we find a hybrid model that works for all parties. This is a problem too big to ignore.