My blueprint (which you should steal) for freeing your time

A few months ago, I started a new job as the leader of a busy team of consultants. Within days of starting, I found myself inundated with meetings, and the expectation seemed to be that I represent our team at board meetings, client meetings, external engagements, you name it.

Being eager to please my new boss, it’s a role I’ve happily played, with little thought to the consequences.

But increasingly I’ve found myself frustrated, compensating for my busy diary by doing all high value work between 06:00 am and 09:00 am, then staying late to mop up the emails I’ve missed during the day — because I’ve been in back-to-back meetings.

While it increasingly appears to be the norm that people work longer hours to keep up, it’s hard to add any real value or critical thought when I spend my days surfing from meeting to meeting. And interestingly, my team has begun to mention that they would like me to provide more guidance on their work, which obviously I can’t do if I’m always in meetings.

It’s been tempting to shrug my shoulders and think “hey, this is just the meeting culture of the organization”. But I’ve realized that this is a lazy response and poor leadership.

Plus, I didn’t take on a new job, just to sit in meetings all day every day — I took the role to learn, grow, and add value through the work I produce.

So, after recognizing that this is a personal problem — i.e. I’m not managing my time well, and that I need to take ownership of it, I’ve implemented a series of steps that have started to significantly reduce the time I spend in meetings. While I can’t promise they will work for everyone, if you’re reading this, it’s my hope that they will be of some benefit to you too.

Step 1: Tell people you’re trying something new on a trial basis and invite them to participate

When I initially began stepping back from meetings, I realized that my lack of attendance was being negatively commented on, and on some occasions being perceived as workshy.

To resolve this issue, it was important that I was clear with my bosses why I was attempting to make this change, and perhaps more importantly, that I believed there were significant organizational rewards that they would gain by my working differently — more time for high-value work, more time to ensure the quality of my team’s work and, increased organizational productivity.

Bottom line, less time in meetings = more time for doing.

To secure their buy-in I positioned my efforts as a pilot, with the goal of identifying techniques that ensure our organization is making the most effective use of staff time. This has reassured my bosses, as they saw it as a temporary measure while the results remain unproven.

What’s more, I’ve found that I’m not the only one struggling with meeting overload, and as such, I’ve invited some other team leaders to work alongside me to manage their overloaded diaries; and identify more effective ways of working. Not only has this created a peer support group for me, where we can share ideas — it’s also helped my bosses see this as a necessary organizational change rather than it being a problem with one employee’s (mine) ability to manage their diary.

Step 2: Set and monitor your productivity ratio

Before making any changes, I wanted to ensure I had a robust way of measuring the effectiveness of my efforts. Enter the productivity ratio.

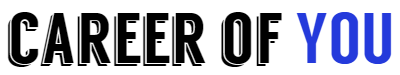

In its simplest form, a productivity ratio segments your typical workday into the time you should spend on specific tasks across an ideal workday. For me my ideal day (based on my current baseline) should be as follows:

Monitoring my daily productivity ratio allows me to identify issues that are preventing me from engaging in deep work, and techniques I can use to drive down the amount of time I’m spending in meetings over the long term.

Step 3: Spend 15 minutes each night pruning your diary for the following day

I’ve found that new meetings tend to creep into my diary over the course of a day unnoticed. To guard against this, the last thing I do each day is spend 15 minutes reviewing my diary for the following day and canceling, or delegating meetings where I can.

Not only does this help me manage my diary for the following day, it also helps clarify what the most important tasks are for the following day, and make a realistic assessment of whether I have the time needed to deliver them. I then schedule those tasks onto my calendar and deprioritize meetings that aren’t going to add much value.

Step 4: Schedule up to two hours of uninterrupted time into your diary (or 90 minutes if that’s all you can manage)

I recently read a blog post by Jeff Weiner, the former CEO of LinkedIn. In it, he mentions that he schedules between 90 minutes to 120 minutes every day of free time, in response to a schedule that was “becoming so jammed with back-to-back meetings that I had little time left to process what was going on around me or just think.”

While he initially felt like holding this time was an indulgence, looking back over his tenure as CEO, he now credits it as the single most important productivity tool he used.

I instantly saw the value in this approach and have started to hold blocks of time in my own diary. But rather than simply put “hold — no meetings” I’m making it extremely clear what I’m holding the time for, by putting the project name in the diary invite. This is helping me protect the time and people are aware that if they book over that time, I won’t necessarily have the time that week to review work, engage with the project and drive the work forwards.

There is a clear opportunity cost to people booking over that time, and it has a direct, negative, impact on their work.

Step 5: Have a strategy for dealing with unplanned meetings

With that said, if you’re in a salaried position and not the CEO (sorry Jeff), to some level, you have to accept the nine-to-five is fair game for meetings. So, it’s necessary to have a plan for new meeting requests that come in on any given day. There are a couple of ways I’m managing this:

· I know I’m more productive in the morning than in the afternoons, so I try to push ad-hoc meetings to after lunch.

· I make a judgment call on which meetings I accept — if it’s one of my bosses who understands why I’m holding the time but still insists on a meeting I typically have to go with it. But for colleagues and direct reports, I find I can often reschedule meetings for a time that works better for me.

Step 6: Delegate meetings by standardizing how information is captured

I’ve increasingly noticed that there are several meetings on my calendar where non-attendance isn’t an option, but I don’t always need to attend personally. Delegating those meetings to others in my team is often a great move: it frees up time on my calendar and gives someone else a chance to gain exposure to key stakeholders.

For delegation to work consistently, I’ve realized that there must be a system in place for consistently capturing meeting discussions and actions. In my team, we’ve done this by establishing a simple word-doc template that includes the following:

- Who attended the meeting?

- Why was the meeting called/what is the problem statement?

- What are the 3–5 key takeaways from the discussion?

- What are the action items?

Step 7: Don’t meet to problem solve — ideate in writing

As consultants, a lot of the work we do in our team is problem-solving which requires a lot of intellectual creativity. A knee-jerk reaction in our organization is to set up workshops with various experts, bringing people together to discuss an issue.

This is a huge time suck as it requires the development of pre-reads, chairing meetings, attending prep meetings, running workshops, and capturing the outputs in meeting notes.

Like all organizations, we are increasingly hybrid, with most employees being in different locations on different days. Learning from fully remote organizations we’re increasingly starting to ideate in writing.

This works by an individual with a problem circulating a shared document with their initial thoughts to key stakeholders, who can then comment on the document or add in additional narrative without the burden of version control.

This has been a game-changer for our team and has produced several immediate benefits:

· The quality of thinking has improved: written responses have led to more thoughtful, better-researched responses; than when people were speaking ‘off the cuff’ during meetings.

· People seem more willing to share ideas: colleagues appear to be more willing to share initial ideas when they know it’s being perceived as work-in-progress, as opposed to speaking in a more formalized meeting.

· Knowledge capture has improved: ideating in writing has drastically improved our knowledge capture compared to discussions via video calls, where meeting notes are subjective and there is a high risk of important messages being lost in translation.

Step 8: Set up office hours

Stealing from knowledge workers in the academic sector, I’ve started to keep office hours — essentially, a regular period that is carved out for ad-hoc meetings should members of my team require additional time.

I hold these one afternoon per week, so they don’t take away from my most productive time in the mornings, and keep each session to 20 minutes so I can meet as many people as possible.

Having a dedicated weekly slot ensures I’m available to colleagues that need me, but also ensures people don’t take up space at inconvenient times in my calendar.

Step 9: Set a high bar for people to call ad-hoc meetings

For people in my team, I’ve put in place a policy that ad-hoc meetings cannot be called without the organizer first developing a 300-word problem statement (setting out the issue the meeting is seeking to resolve) and a clear agenda for how the meeting will arrive at a solution.

The results of this policy have been interesting. Some colleagues have balked at the admin burden required for them to call a meeting, but positively, this typically leads to them not scheduling unnecessary meetings. Others have reported that by writing their problem statements, they have realized that it would be more effective to circulate a shared document to solicit feedback rather than hold a meeting.

The key to making this policy stick has been to lead by example, and only call meetings myself once I’ve developed a problem statement and considered whether a meeting is the most effective way to arrive at a solution.

Step 10: Batch and hack your meetings

Lastly, and forgive me for stating an obvious tactic, but as part of my nightly calendar review, batching and hacking my meetings has helped. If a meeting is 60 minutes, I’ll make it 45 minutes. If 30 I’ll make it 20 minutes. I try to group meetings where I can. And if I’m not able to influence the length of the meeting, I’ll try to just attend for specific agenda items where I’m needed.

I’ve found that some people have initially felt uncomfortable about having less time to discuss things — but it does seem to focus conversations and free up additional time.

Parting thoughts

By implementing these tactics, I’m beginning to see a shift in where I spend my time each day. I feel more in control of my time and think much more carefully about how I’m allocating it.

No one goes to work to spend the majority of their time in (often unproductive) meetings — and if a job advert said you’ll spend 30–40 hours a week in meetings, I bet you wouldn’t even apply.

We go to work to create something, achieve an organizational mission, learn, and grow. I hope these techniques can help you too, in taking back control of your diary and better utilizing your time.